What You Know

Students have heard me say a crock full of seemingly incongruous things over the years. While I’m aware of the head scratching and confused looks shooting back and forth in the classroom whenever I start “speaking outside of the box”, those little gems always make perfect sense to me. I’m also aware of the fact that that probably says more about me than it does my students.

One of those ditties was particularly relevant during my time at CDIA, where there no longer exists an amazing opportunity for photo students to rub shoulders on a daily basis with those working in design, animation, digital filmmaking, and sound. Pity.

I used my directorship at CDIA to drive home the widely acknowledged point that the new media world that my students were attempting to enter was no longer photo-centric, that convergence had happened while we were all out “taking pictures” and that theirs would more than ever be an integrated role in a digital food chain that is now known as “content creation”. They would either have to learn to work with or for other media artists or, what’s becoming more and more likely due to expanding expectations and shrinking budgets, learn to incorporate many of those skillsets into their own. I implored them to understand that it would be in their best interest to learn how critical it is to at least be conversant with what other creatives are up against before they got out of school and had the lesson taught to them the hard way. Then I built a program that gave them a taste of what I was talking about.

So we integrated students, faculty and projects between programs so that photo students were formally exposed to the challenges faced by graphic and web designers and videographers (and vice versa). I believe it prepared all of them to better compete for the types of clients available to them, not the types of clients their older instructors like me used to work with back before electricity.

It was a privelige to be able to drag career design and video professionals like Peter Kery or Howard Phillips into my classroom to back me up. Sadly, with the collapse of the business that provided a (leaky) roof over our creative collaboration, that privelige is now history.

But the fact of convergence remains, and career-focused students everywhere are beginning to get the message.

Then there’s the issue of authenticity.

So many rookie photographers say that they don’t know what to photograph, they don’t have any ideas of their own, so they simply copy what’s already been done. Don’t get me wrong- imitation is one of the ways we learn. Like almost every other photographer who came of age in the 60s and 70s, I wouldn’t have spent my working life working with a camera if I hadn’t first seen the work of Robert Frank and Lee Friedlander, and then spent years trying to reshoot their pictures.

Imitation is like the steady parental hand on the bicycle seat that helps us learn how to ride a two-wheeler. But eventually, big boys and girls tell mom or dad to let go so they can ride off in their own direction. And while the direction may not be so unique, what each of us see, feel and experience on the ride is.

As a matter of fact, Henri Cartier-Bresson, among the most copied photographers ever, said it this way about 40 years ago:

“I don’t know what it means to be dramatically new. There are no new ideas in the world, there are only new arrangements of things. The world is new every minute…it’s falling to pieces every minute.”

and

“Life is once, forever.”

Statements like those are what keep photographers like me out on the street, out in the world, out on the hunt. Pictures are everywhere, all the time, and when we let them in, they can be filtered through our world view and our state of mind. They can be ours, uniquely.

But when a student hears that and is still looking for ideas, my first advice is to start with what writers have always been told:

Write (shoot) what you know.

It’s always been a good place to start- by limiting a student to the seemingly tiny, insignificant box called “your own experience”, most are amazed at the infinite potential within.

Sure, they don’t come out of the gate making the kinds of important work that raises awareness of serious things like illness or homelessness, unless those issues touch their lives in some way. Those pictures come later. But it does give them the access and experience necessary to dig deeply into a subject with which they are uniquely and intimately familiar.

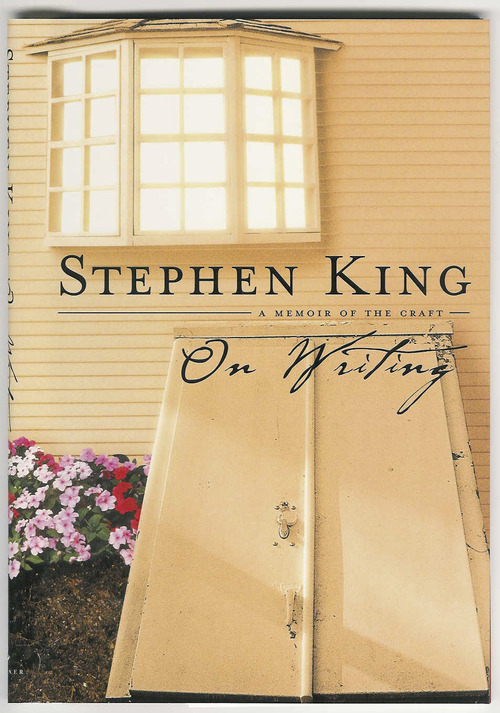

Then, a couple of days ago, I downloaded a book I’ve been meaning to read for years. It’s called On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft, and it’s written by Stephen King.

And every one of you reading this should read that next.

Because he has a better take on it. And whether or not you care for Stephen King, or about writing (or even reading) every idea in the book is as pertinent to photographers, designers, filmmakers, artists, as it is to writers. And there are alot of big ideas in this small book.

“The dictum in writing classes used to be “write what you know.” Which sounds good, but what if you want to write about starships exploring other planets or a man who murders his wife and then tries to dispose of her body with a wood-chipper? How does the writer square either of these, or a thousand other fanciful ideas, with the “write-what-you-know” directive?

I think you begin by interpreting “write what you know” as broadly and inclusively as possible. If you’re a plumber, you know plumbing, but that is far from the extent of your knowledge; the heart also knows things, and so does the imagination. Thank God. If not for heart and imagination, the world of fiction would be a pretty seedy place. It might not even exist at all.”

“Write what you like, then imbue it with life and make it unique by blending in your own personal knowledge of life, friendship, relationships, sex, and work.“

There you have it, boys and girls. I’ll let go now so you can ride off on your own.