Yes

Duane Michals’ career retrospective is about to go up at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, and I, for one, can’t wait to see it. I’ve bumped into Michals a number of times in my career, and have loved his work ever since I bought my now-tattered copy of Real Dreams at a Ritz Camera store in South Jersey in the mid 70’s. Signing it for me a decade later after a lecture at RISD, he said “where did you ever find this?” When I told him it was one of the books that showed me what it meant to be a photographer and an artist, he looked at with me with exaggerated pity and said “I’m so sorry to hear that”.

Earlier today I was rearranging my too big collection of photography books to make room for some recent acquisitions: Extraordinary Circumstances, David Hume Kennerly’s excellent documentation of Gerald Ford’s presidency; Marion Post Wolcott, a collection by my favorite lesser known FSA photographer; and a somewhat disappointing overview of Bruce Gilden’s street photography (disappointing because of the work, yes, but mostly because it’s too big to fit on the shelf).

Michals, now in his early 80s, has published dozens of books over the past half century, more than a few of which I own. Looking at them on the shelf, I suddenly remembered another short conversation I had with him. I pulled out my copy of Album: The Portraits of Duane Michals. Opening it revealed a 25 year old inscription, written in blue ball point pen:

To understand what "yes" means, I have to take you back a few years.

If you subscribe to the notion that the announcement of Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre’s process in 1839 marked the “invention” of photography, then we have just passed our medium’s 175th year. Now, Joseph Nicephore Niepce, William Henry Fox Talbot, or maybe even Thomas Wedgewood might each challenge you to pistols at 10 paces if you do, but let’s leave that one alone for now.

But like the Kennedy assassination, the Challenger explosion, 9/11, and the tempest in a tit-slip resulting from Janet Jackson’s Super Bowl wardrobe malfunction 10 years ago, I remember vividly where I was on photography’s last big birthday, when it turned 150.

It was 1990, 25 years ago, and I was back in my hometown of Philadelphia to attend a major conference marking photography’s sesquicentennial year. I was lured to the shindig on the campus of the University of Pennsylvania by the promise of a weekend spent rubbing shoulders with some of the biggest names in the photo art and academic world. They all converged on Philly to speak about their work, both in the long context of history and in the turbulent present tense of the post-Reagan conservative political climate. One by one, iconic photographic artists and influencers took the stage and made a case for their little point along the timeline of the history of our medium.

Candy Cigarrette ©Sally Mann

Sally Mann, fresh from her breakthrough book At Twelve (but still a year or two away from the controversy that would arise from publication of the ambiguously nude photographs of her young children featured in Immediate Family) spoke at length about the firestorm surrounding Senator Jesse Helms, The National Endowment For The Arts (NEA), and an infamous, posthumous exhibition of photographs by Robert Mapplethorpe, who had recently died of AIDS. Censorship of publicly funded artists like Mapplethorpe was clearly the number one issue on everyone’s minds, and none more so than Mann. She spoke quietly, and even a little nervously, about the FBI raid on Jock Sturges’ studio earlier that year and the confiscation of much of his equipment. Sturges makes large format portraits of naturist families and their adolescent children in California and coastal France, and was being pursued by law enforcement over allegations of child pornography. After a lengthy legal battle, he was never charged.

Feast of Fools © Joel-Peter Witkin

Next came Joel-Peter Witkin, who works with corpses, and parts of corpses. His shocking, classically composed tableaux remind me of something cooked up by a mortician who also happens to like to play with his food. The lights dimmed, Witkin, dressed in black, took the stage and began to speak in a slow, low voice as an almost unspeakable series of imagery flashed behind him. I wanted to look away, to walk out, but I stayed. So did most of the rest of the audience. Perhaps what kept us all staring quietly from our seats was the same morbid fascination Witkin felt as a child when he witnessed a young girl’s head rolling toward him in the street after a horrible traffic accident. I remember being repelled by Witkin and his work at the time, although I wonder if I would feel differently today with a quarter-century’s worth of perspective. Everybody knows Matthew Brady and the boys were notorious for dragging around bodies of dead soldiers to make more effective battlefield compositions during the Civil War, but, c’mon, at least those guys had the decency to refrain from arranging, however artfully, a fruit and cheese platter in that poor, dead Confederate sharpshooter’s abdominal cavity!

I remember asking myself, naively perhaps, what the fuck was going on with photography all of a sudden? When did so much of it become so narcissistic, disingenuously provocative, ill-mannered and even nonsensical? When did it become such a big, fat FUCK YOU to anyone who didn’t get it, or worse, didn’t buy into the artspeak required to join the ranks of those who did? What happened to subtlety, to cleverness, to all those lovely “decisive moments” captured by photographers who let their photographs do the talking for them?

If, in Kerouac’s words, photographers like Robert Frank “sucked a sad poem right out of America onto film, taking rank among the tragic poets of the world”, 30 years later Robert Mapplethorpe stuck a bullwhip up his ass, snapped a picture, and, whether intending to or not, sucked a sad and tragic polemic right out of the American political and religious right, pissing in the pool of public funding for the arts in a way that I'm sure was never imagined.

But it soon got better.

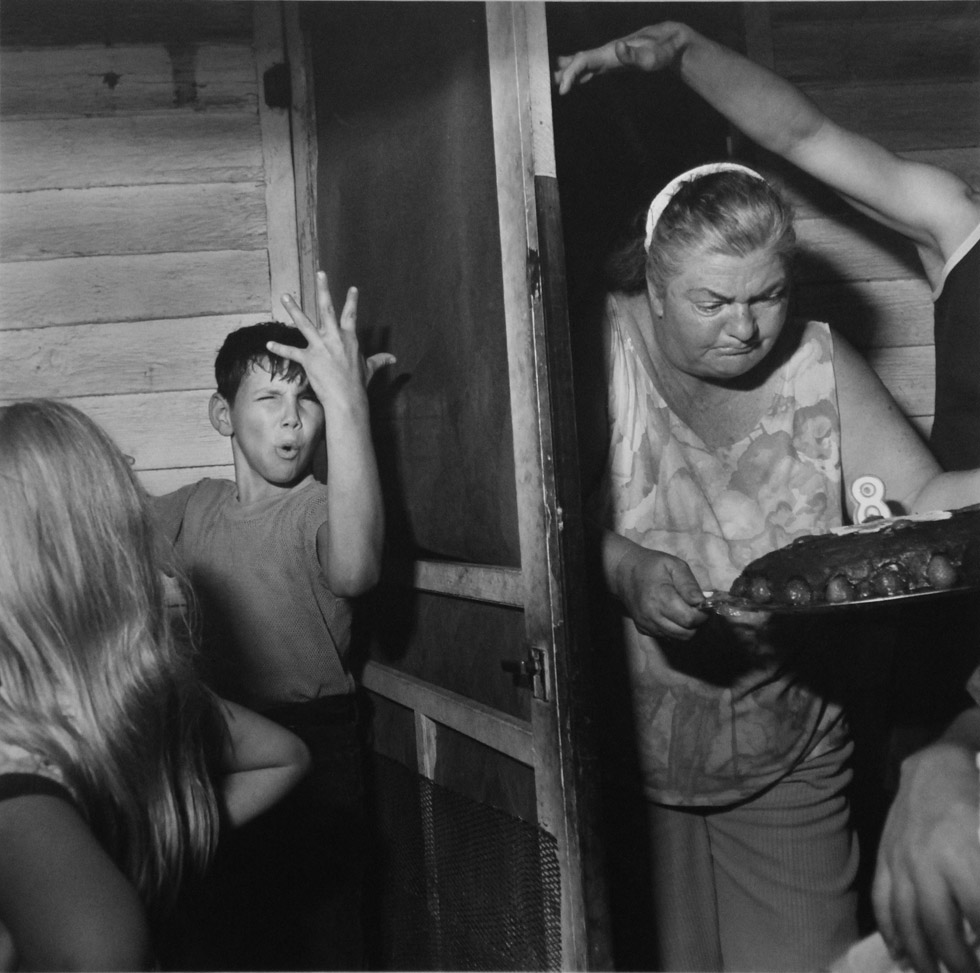

© Larry Fink

Larry Fink presented a powerful collection of images from his first book Social Graces. Fink is a Bard professor and documentarian whose best known work contrasts upper class Manhattanites enjoying (or at least tolerating) their parties, debutante balls and nightclubs against parallel social events in the economically-distressed, rural Pennsylvania village of Martin’s Creek. After his presentation I had the opportunity to speak with him one-on-one for a few minutes, and he told me about his latest project, a similarly divergent pair of portfolios playing off Wall Street trading floors against inner city Philadelphia boxing gyms. Referring to the peculiar strain of pugilism he photographed on Wall Street, he told me he “hated those bastards”. Today, Fink simply says “Twenty-five years ago I had hope; now I have fortitude.” About a new edition of Social Graces, Fink writes that he offers additional photographs from that era “as a gift to those who believe that time stopped deftly in a magnetic moment lives on … and on.”

“Time stopped deftly in a magnetic moment…” I’ve never before heard a better description of what photography as I know it and love it can be, and I’d never heard of Larry Fink until that day. But looking back over all these years, he impressed me more than just about anyone else at the conference.

If Witkin, Mann and the right wing assault on the NEA and public funding of the arts were all downers, the star of the show, Duane Michals, was irreverently hilarious. He was the guy I came to hear, and he didn’t disappoint. He also didn’t show any pictures, either. “I was halfway down here on the train from New York this morning” he told the adoring crowd, “when I realized I forgot my tray of slides.” He then went on to tell about an hour’s worth of dirty jokes. It was just what the room needed after so much…gravitas.

Now, about that “yes”. Late in the afternoon, during a break in the proceedings, I hovered around the edge of a small group of people who had buttonholed Michals at the back of the hall. They were all very passionately voicing their outrage over the Mapplethorpe/Sturges/Helms/NEA debacle, and were each sharing personal insights of their own experiences with censorship. I was fascinated by the discussion, even though I was a little out of my depth (I just wanted Duane to sign my book). He sensed that, and reached out to take it. As he did, I took a deep breath and asked the questions that had been on my mind all weekend.

“Aren’t artists who seek out public funding inviting censorship? Isn’t it logical to expect that something like this will become politicized once taxpayer money gets involved? And, should the government even be in the business of funding artists in the first place?”

He stopped for a second, looking at me as if he was trying to figure out just who this numbskull thought he was to ask such an impertinent question at such a distinguished gathering of like minds. Returning to the conversation without answering my questions, he scribbled something in my book and handed it back to me. The answer was right there, in blue ink, but to which question I will never know.

Randy.

Yes,

Duane Michals