The Hard Part

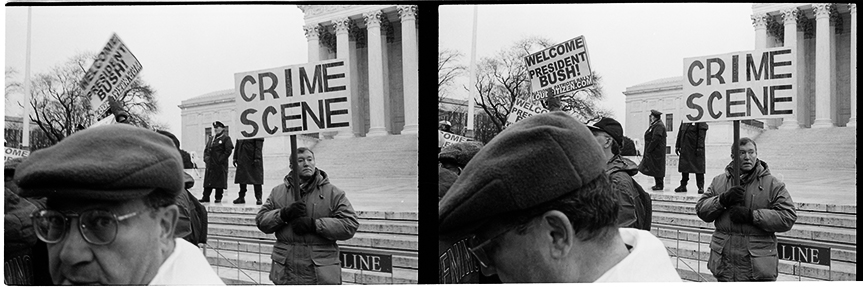

Pictures like this drive me nuts. I call it Meanwhile, Back at the Supreme Court. It captures the boisterous scene outside that building as right and left wing demonstrators clashed after the contested election of 2000. While all this was happening, President George W. Bush was delivering his first inaugural address in the background over loudspeakers. It was an exciting and historic experience to witness and document, but until now, I’ve never shown this image to anyone. As a matter of fact, it didn’t even exist until last night.

The reason? It’s fake. The moment it depicts never happened.

As anyone can plainly see from this pair of film frames shot just seconds apart, the image is a composite of two moments that actually did happen. The frame on the right is the one I’ve always printed and shown, chosen because of the apparent anxiety and nervousness of the policeman looking one way and the man holding the “Crime Scene” sign (reflecting his opinion about the outcome of Bush v. Gore) looking the other.

But it’s the guy in the foreground looking down that sometimes causes me to lose sleep at night. As much as I like the shot as it is, I knew I also had the less successful but nearly identical frame with him looking up at me suspiciously. I knew that I could easily and invisibly combine the two frames to make a much better picture, and that nobody other than me would be the wiser. Even though I knew it would hurt and that I probably wouldn’t respect myself in the morning, last night I finally went all the way. I did it to prove a point about how hard it is to be a good photographer.

Making the composite wasn’t the hard part — after all, any exceptional 5th grader photoshopping at the 7th grade level could pull this off with a layer mask and a 5 minute attention span. The hard part has always been not doing it.

The hard part is admitting that maybe I missed the shot and need to try harder next time. The hard part is trying to continually hone my wits and reflexes in order to better capture moments the way they actually happen instead of relying on software skills to manufacture more perfect ones after the fact.

The hard part would be understanding that as innocuous as it may seem to just go ahead and strip the guy on the left into the frame on the right and pretend that I shot it that way, doing so would forever redefine my own relationship to everything I cherish about photography.

There is no right or wrong here, but there is a difference — and to me, it’s a really big one. While I drank the Kool-Aid 20 years ago when it came time to embrace digital cameras, computers and software, I hope to always keep the dregs floating forever in the bottom of the cup, at least for these types of shots.

The hard part is hard indeed–if it were easy, everybody would be doing it, and I’d be creating short video tutorials using pictures like these to demonstrate how to use Photoshop to make good pictures perfect. I’d be posting the shot on some forum somewhere asking my fellow gear-heads whether the superb but outrageously expensive 35mm Summilux ASPH would have resulted in creamier bokeh than the incredibly sharp but more affordable 35mm Summicron (pre-ASPH but German, not Canadian) bolted on the front of my 0.72, non-TTL M6 (chrome over magnesium alloy, not black paint over brass). I’d hold it up as proof of the superiority of digital over film, or film over digital, or something over something else. That’s what everybody else is doing, right?

None of this is meant to suggest that I’m immune to the temptations — far from it. I made a living for many years as a commercial photographer making Photoshop composites and photo-illustrations for catalogs and advertising. I’m actually struggling right now to not simply delete this blog post before I put my self-righteousness and hypocrisy on the record.

I’m trying to not just put the damn composite on my website and get on with things. It’s so tempting because I can now see with my own eyes that it’s as good as I always thought it would be and much better than the original. And I know that I have many other really good shots that could be made perfect just as easily.

Today, I’m a commercial photography teacher, not a commercial photographer. In addition to helping students learn the basics of exposure and lighting (and yes, even Photoshop compositing), I try to get them to think about trickier concepts like commitment and intention and restraint.

When one of them asks me how to remove a distracting element from a photograph that they should have seen through the viewfinder, my first response is usually “look more carefully at what you’re shooting next time” or “wait a half second longer before you push the button”, stuff like that. But my second response has to be to then fire up Photoshop and show them how to get rid of it.

We’ve all seen the pinched pyramids that embarrassed the very pinnacle of pure photographic aspiration, National Geographic. OJ Simpson’s heavily doctored mugshot on the cover of Time forced the credit line “Photo Illustration by…” into the journalistic lexicon whenever a news publication dares to go anywhere near Photoshop. I don’t pretend to be in either league, and neither is my wordy little freakout here about protecting the integrity of my pictures or my process.

Nobody’s going to fire me or banish me to some god-forsaken digital whorehouse where I can screw around with whatever other prostituted pixel-pushers strike my fancy. But digital photography does not necessarily have to go hand-in-hand with Photoshop trickery. Even the purest purists among us can adapt the new tools to fit our methods — it doesn’t have to be the other way around. In my own very humble opinion, seeing clearly, working simply and editing brutally is everything.

The photography that I do now and that I hope my students can appreciate still celebrates the pure intellectual pleasure of capturing something interesting with a camera without adding, subtracting, multiplying or dividing any of it. I was inspired early on by heroes like Frank, Erwitt and Friedlander, each of whom went out into the world with little more than a Leica and a worldview and came back with remarkably unvarnished examples of how much there is to look at if we can only learn to see it well first.

Because we feel the need to have to brand everything these days, all that “walking around with a camera” stuff is referred to as “street photography” or worse yet, “fine art photography”, but to me, it’s always been simply “great photography”.

I don’t think that the sea change in technology precludes any of us from continuing in that tradition, if we choose to do so. In many ways, the digital revolution has made so much of what we do so much better. But we have to continue to push back against some of the temptations that new technologies dangle in front of us. We have to keep trying to get really good at the hard part.

The other day I was listening to one of my young instructors describe some fabulous new, state-of-the-art automated HDR technology that renders far more impressive digital video footage than ever before. “You can’t control it, they won’t need us much longer, but it’s beautiful. This is where everything’s going” he sighed, with the geeky resignation of a gun nut facing a firing squad.

“I know where it’s going”, I replied with a different kind of resignation. “But it’s not taking me with it”.

Elliott Erwitt has an opinion on this, too!